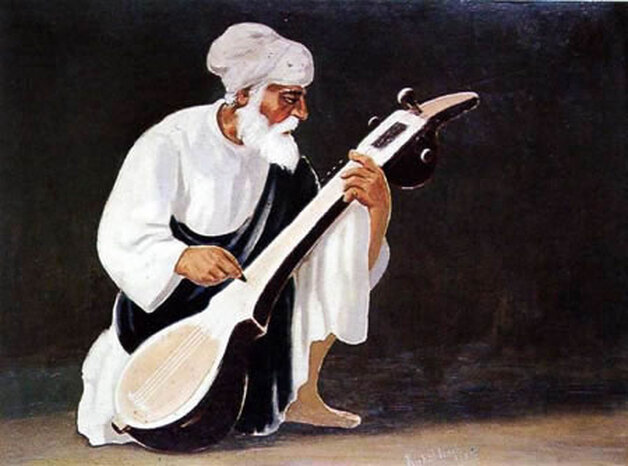

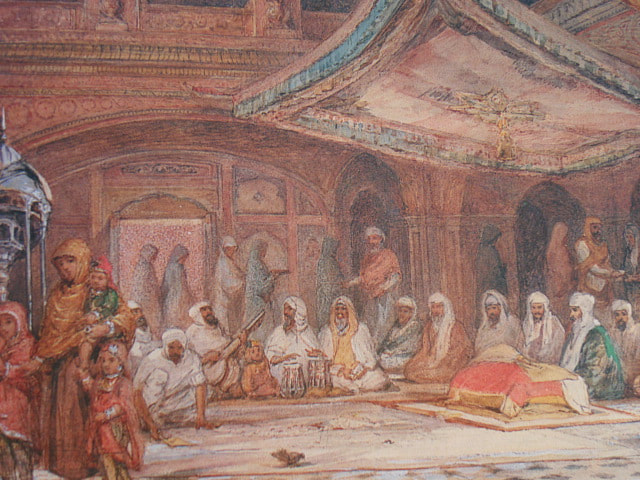

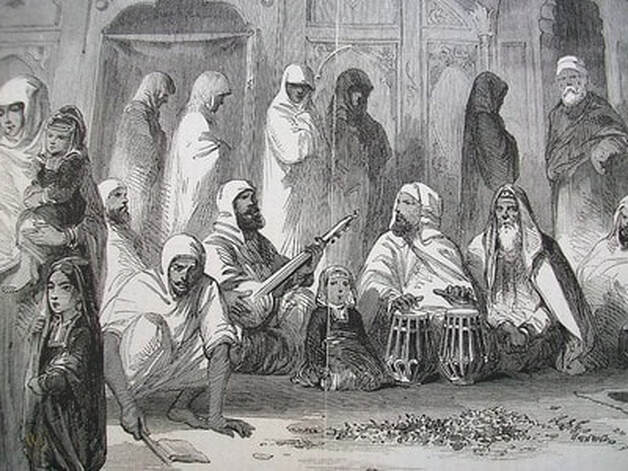

A journey through Sikh Musical HeritageMusic is a core part of Sikhi, and having learned the harmonium from a young age, it's something that fascinates me. However, the vast majority of Sikh music you hear today uses neither the traditional instruments of the Sikhs, nor is it sung in the way the Gurus intended the compositions to be sung. This point, as well as the evolution of Sikh music, is beautifully explored in a new documentary on Amazon Prime called the Sikh Musical Heritage - the untold story. This article is my review of this award winning documentary. Why music is important to SikhsThe Guru Granth Sahib, for Sikhs, is our living teacher. It contains the compositions of our Gurus as well as other enlightened individuals from different faiths and backgrounds. The Guru Granth Sahib is composed in 60 raags (a structure of melody), and so logically, you don't speak the compositions within the Guru Granth Sahib, but you sing them. Each raag is supposed to elicit a certain mood or response from the singer and listener, and when done perfectly, it provides the perfect platform for an individual to connect with the one energy through meditation, as well as helping the individual navigate every day life. It is meant to be both practical and spiritual. In Sikhi, music isn't an aid or a tool, it's a core part of the Sikh way of life, and so learning an instrument to help us connect with the one energy is an important part of a Sikh's life. My experience with Sikh musicI grew up learning the harmonium, also known as a vaja (or a baja if you're a Doabi like my family). I first picked up the instrument when I was about 4 or 5 years old, and for the next decade I would attend a weekly class in the English Midlands with a group of about 10/15 friends. For me, at that age, it was a great way to see my friends, and we would all look forward to the end of class so we could play football. As kids, you don't always realise why you're learning something, and the reward of football kept me going to Sikh music classes (known as Kirtan, or Gurmat Sangeet). I was one of the few that learned the harmonium, the tabla was considerably more popular, but I liked the harmonium and I loved singing. As I entered my teenage years, it felt like an incredible way to express myself, and get rid of stress and tensions. I also began to connect more with the Shabad, the words that I was singing. Gurdwara politics put an end to our classes when we were about 15 years old and after that I would learn on and off, but in terms of my musical progress, it more or less stopped then. For several more years, I continued using it as a way of connecting to my Guru, but toward the end of my teenage years I came across knowledge that shook my worldview. My awakeningAt that age, I was a sponge for knowledge, and would spend hours learning about all sorts of subjects - and it was when I went down the rabbit hole of Sikh musical history that I found things out that altered my perspective. In Gurdwaras around the world we are used to seeing the harmonium and tabla. So much so, that I thought these were the Guru's own instruments, being used to sing the shabads of Guru Granth Sahib and Dasam Granth. So when I found out that the harmonium was a French invention shipped off to India following the British conquest of Panjab and then used as a tool to disconnect us from our heritage, I was pretty pissed. Instead of seeing the harmonium as a tool to connect me to my faith, I saw it as the tool of the coloniser to separate me from my culture. I began to resent the harmonium, and for years it was hidden away at home, collecting dust. I set out to find out more about real Gurmat Sangeet, and the first time I heard the rabab I knew that I couldn't listen to kirtan being done with a harmonium ever again. Whenever I now hear kirtan done with a harmonium, it sounds so flat and devoid of emotion. The truth is, I should have realised a long time ago. I remember when I was younger the first time I heard a Dhadhi Jatha sing vaars (literally strike of a weapon, also known as a ballad), I was completely mesmerised. I couldn't understand many of the words but I could feel the energy and emotion of what they were singing, and I loved it straight away. But back then in England, if you were learning kirtan, you either learned tabla or harmonium. It was these dhadi vaars that were so well modernised in the early 2000s by Immortal Productions and British Dhadi Jathas from the Midlands like Jagowale and Pasla Dhadi Jatha that connected a whole new generation of Sikhs with Dhadi music. As I delved deeper into my journey I came across the beautiful sounds of the rabab and the sarangi. I began to hear the words of the Gurus being sung in the way and the form the Gurus intended them to be sung and the music felt like it had awakened me. I came across Sikh groups and sampradayas who had kept the tradition alive, first in secret, and then, more openly. It felt like seeing in colour after the black and white of the harmonium. Being somewhat familiar with Sikh musical history, I was pretty excited when I heard about a documentary that explores this history in more detail. The documentaryThe documentary, just over an hour long and available to watch on Amazon Prime Video, covers the evolution of Sikh music in chronological order. It begins with the very first Sikh instrument, the rabab, commissioned by Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith, and played by his companion Bhai Mardana. This particular rabab, known as the Firandia Rabab after the individual who built it (Bhai Firanda), was special in that it was a five-stringed rabab rather than the standard six-stringed version to specifically play the compositions of Guru Nanak. The documentary then explores the other instruments the Sikh Gurus used to reflect the compositions they created. These include the saranda of Guru Arjan Dev which was specifically modified by the Guru with three-strings to sing dhur ki baani or the creative composition to awaken the soul and connect it with the one energy. Another instrument customised by Guru Arjan Dev Ji is the jori, a type of twin drum which was an evolution of the pakhawaj, a single drum. It's similar in appearance to the modern day tabla, but with a greater bass that aims to provide a calm, healing property to accompany the calm of the saranda. After this, we're introduced to the sarangi, customised specifically by Guru Hargobind to sing the 22 vaars in Guru Granth Sahib. While the saranda of Guru Arjan Dev Ji provides spiritual energy to bring calm and peace, the sarangi of Guru Hargobind provides bir rass (a warrior spirit). The taus, an instrument I wasn't familiar with, is covered next. The taus, meaning peacock (pictured above), was introduced by Guru Gobind Singh and provides a beautiful, mellow and melodic sound. The taus was further modified into the dilruba, a smaller and lighter instrument which allowed Sikhs to carry it everywhere. The documentary actually provides records of Sikh fighters who took their dilrubas onto the battlefield during war, such was the importance of their connection to these musical instruments. Finally, the documentary explores the impact of colonisation on Sikh music. It makes the argument that the British aimed to disconnect the Sikhs from their heritage with as little friction as possible, the aim being to change the Sikh worldview and identity without the Sikhs realising any change was happening. Some changes happened very quickly - Sikh art failed to evolve following the fall of Sikh rule, and Sikh education was replaced by western education, the impact being the end of universal state funded education by the Sikh state and a massive fall in literacy rates in Panjab. Sikh music, being such a core part of the Sikh psyche couldn't be replaced wholesale, but the introduction of the European style harmonium under the guise of modernity changed the connection Sikhs had with their Guru irreparably. This is similar to weaponry which, again, as a core Sikh practice, couldn't be discarded, but if we think of Sikh weapons, they don't evolve much after the mid-19th century. The spiritual and warrior side of Sikhs was curtailed. The documentary is clear that the introduction of the harmonium was an important part of British policy to pacify the Sikhs and anglicise them. And it seems to have worked much better than they could have imagined. The skill of singing in raag is largely lost in the Sikh mainstream, while almost every Gurdwara in the world uses the harmonium as its default instrument. The completeness of disconnecting Sikhs from their Sikhi dharam, and repurposing it into the anglicised Sikhism is reflected in modern day Sikh institutions like the SGPC (the hopeless governing body for Sikh Gurdwaras) and the continuing habit of seeing the Sikh 'religion' through an Abrahamic lens. The documentary continues by exploring how traditional Sikh instruments are made and ends on a more positive note. It shares the importance of reconnecting with traditional Sikh instruments and singing the compositions of the Guru Granth Sahib in the way they were written. The documentary ends on a group of British children learning the dilruba and points to a more hopeful future. My thoughtsThe documentary is produced by the excellent Wootz organisation. They're a British Sikh organisation I've been familiar with for a while (largely due to their clothing line) and the production quality of the documentary is fantastic. Sikhs in the western world are beginning to mature in the way we use technology to connect with each other and our beliefs, and having such a well produced documentary feels like an massive step up. The documentary sources experts, academics, historians and musicians from around the world, and they're able to explain the concepts of Sikh musical heritage in both English and Panjabi. The core technical input is provided by the London based Raj Academy, and there are experts and musicians from the UK, Panjab, Delhi, the United States, Canada, Germany and Spain. The passion of the musicians is contagious, and they're able to express this love very clearly and articulately. The documentary flirts with the technical underpinnings of the raags, without going into too much detail about each raag. It manages to strike the perfect balance of being digestible and easy to understand, while stoking the curiosity of viewers to explore the concepts they introduce in more detail. I came away from the documentary very impressed and pleased that more people are paying attention to the deep musical heritage of the Sikhs. I was aware of some of the concepts in this documentary, but there was a whole bunch of information I was unaware of, or less exposed to, and so I came away feeling I'd learned a lot. It's a good watch, and at just over an hour long, it's quite an easy watch as well. I was absorbed in the documentary and they seem to have sourced the right experts who explain things very clearly. It's interesting to see the growth of the diaspora. The first generation or so had to work hard to try and fit in and earn a living in western countries, but the second and third generations are working hard to ensure we don't lose the connection to our roots. While organisations like the Raj Academy try to reconnect us to our musical heritage, other groups and individuals, like Wootz, are working to re-establish our connection with other 'lost' Sikh practices. A perfect example was the Toor Collection, an exhibition on Sikh history in Central London (and you can read my review of that here). It really does feel like a bit of an awakening. Finally, in terms of my own views on Sikh musical heritage, I think it's important that Sikhi continues to evolve, and this means welcoming new instruments and ways of expressing Sikh thought. But that can't be at the expense of losing our connection with the Guru. Singing shabads with the Guru's own instruments, in the way the Gurus intended through their raag compositions needs to be the default. This is how we connect with our Guru and should be the way the Guru Granth Sahib is communicated in Gurdwaras. However, experimentation with non-Sikh instruments like guitars, keyboards, and the harmonium needs to be accepted to allow new generations to express themselves - not as a way of replacing raag kirtan - but to complement it. The thing is, right now, the balance is completely the wrong way around, with traditional Sikh Gurmat Sangeet a dying practice. Until we're able to reconnect with our musical heritage, we will always be under a colonial mindset. Where can I watch this documentary: Amazon Prime Video Running time: 1 hour 9 minutes Recommendation: Must watch Comments are closed.

|

AuthorBritish Sikh, born in the Midlands, based in London, travelling the world seeing new cultures. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

Photos from Johnny Silvercloud, Nina A. J. G., Michael Vadon, jcorrius, mikecogh

RSS Feed

RSS Feed